- Bardic Knowledge

- The Early Bards

- Initiation

- The Bardic College

- The Roots of Druidry

- The Wheel of the Year

In the Celtic Tradition, the term Bard describes a wordsmith or linguist with particular skill in poetry, songwriting or storytelling. The Bard’s job is to take the audience on an ecstatic journey using the power of words.

“There are among them composers of verses whom they call Bards; these sing to instruments similar to a lyre, they applaud some, while they vituperate others.” — Diodorus Siculus, Histories, V, 31, 1st century BCE

“The Bard is both a creative artist and a custodian of lore and tradition, a scholar, poet, composer, performer, musician, storyteller, historian, and mythographer. The central principle of the bardic path is communication, chiefly through word and sound.”

– The British Druid Order

“A true Bard must know the following: music (and the playing of a period instrument, preferably Harp), poetry (original, and other people’s), song (original and other people’s), the History, Law and Custom of his/her Kingdom, as much knowledge of mundane medieval history, Law, and custom as they can possibly learn, and at least a very basic knowledge of linguistics and alphabet/cyphers. Some training in Folklore, and in the arts of Sociology and Semantics would help, too. A reasonable amount of heraldic knowledge would not be out of place, either. The Bard should investigate the “Matter of Britain” very thoroughly, paying special attention to Sir Gawain, and to Arthur’s Queen. Bards do not just sing songs! They recite, and write poetry, stories, tell myths, but the operative word here is that they ‘speak’.”

– Ioseph of Locksley, OL, Pel, &c. © 1989, 1990 W. J. Bethancourt III

“A Bard has a responsibility to study relevant material, in particular, the traditions and stories of the Celtic path we are seeking to revive.”

– Dearbhaile Bradley, Elder Bard of Gorsedh Ynys Witrin.

Bardic Knowledge

Bardic colleges were effectively the Arts department of the Druidic ‘University’ and historically issued degrees in the style of Bachelors’, Masters’ and Doctorates. Bards were expected to know all the relevant stories of their tribe, the works of the ancient Bards, the histories, the pedigrees and heraldry, as well as the laws and metres of poetry and harmony. They were expected to have a fine voice and the command of an instrument. The college is further sub-divided into the schools of Poetry, Music and Heraldry (which includes storytelling). The common element to all schools is the use of words to enchant and evoke. A Bard must have an innate love of language and communication. It is recommended to study at least one Celtic language as it is always better to study Bardic Texts and especially poetry in its original language.

Bardic colleges were effectively the Arts department of the Druidic ‘University’ and historically issued degrees in the style of Bachelors’, Masters’ and Doctorates. Bards were expected to know all the relevant stories of their tribe, the works of the ancient Bards, the histories, the pedigrees and heraldry, as well as the laws and metres of poetry and harmony. They were expected to have a fine voice and the command of an instrument. The college is further sub-divided into the schools of Poetry, Music and Heraldry (which includes storytelling). The common element to all schools is the use of words to enchant and evoke. A Bard must have an innate love of language and communication. It is recommended to study at least one Celtic language as it is always better to study Bardic Texts and especially poetry in its original language.

Traditionally Bards had poetical rights and authority not subject to the control of the monarchy. Typical duties would include: Entertaining the court; Accompanying armies into battle; To applaud the living and record the dead; To praise virtue and condemn vice; Celebrate gifts of fancy and poetry; Perform at funerals, coronations and other solemnities; To carry messages between princes and to declare War and Peace.

In the Welsh Eisteddfod tradition it was unusual to expect the Bard to hold public office as such, the Chair is given as a prize for literary achievement, more like the Nobel Prize for Literature than Poet Laureateship to use two familiar examples. The Welsh “Gadair” or Chair, is actually won by writing a long ode (“awdl”) in strict Cynghanedd (a complex form of internal alliteration and rhyme) on a given annual theme. Competitors enter anonymously under a pseudonym and having won the Chair, may not be expected to do much more than continue to write poetry and stare at the clouds…

The Early Bards

Our cultural heritage, rooted in ancestral tradition, was born and bred within our own indigenous, sacred landscape, and bardism today continues to be inspired by its pagan origins. The first artists, storytellers, musicians, poets and singers were undoubtedly found among the shamans of old, who were practising the bardic arts over 30,000 years ago. Inseparable from both magic and religion, ancient bard-craft was an essential prerequisite for the priestly function in tribal society. Sacred verses, chants and ritual songs were given directly to the shaman by the denizens of the spirit world, of whom the tribal myths and legends told in order to transmit spiritual knowledge. Poetry not only formed the basis of devotional hymns and prayers, but played a vital part in prophecy, healing incantations and spell-making; also facilitating religious ceremonies and shamanic journeys.

Our cultural heritage, rooted in ancestral tradition, was born and bred within our own indigenous, sacred landscape, and bardism today continues to be inspired by its pagan origins. The first artists, storytellers, musicians, poets and singers were undoubtedly found among the shamans of old, who were practising the bardic arts over 30,000 years ago. Inseparable from both magic and religion, ancient bard-craft was an essential prerequisite for the priestly function in tribal society. Sacred verses, chants and ritual songs were given directly to the shaman by the denizens of the spirit world, of whom the tribal myths and legends told in order to transmit spiritual knowledge. Poetry not only formed the basis of devotional hymns and prayers, but played a vital part in prophecy, healing incantations and spell-making; also facilitating religious ceremonies and shamanic journeys.

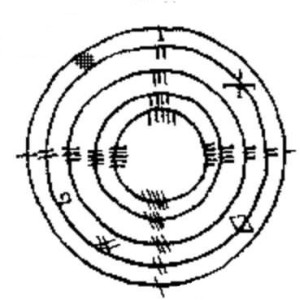

In oral folk tradition, inspired by the earth herself as a living Muse, Druids of the Celtic priesthood used the bardic arts as their primary teaching medium. Druidic Bards committed occult lore to memory using the secret language of the Ogham. Each seed-syllable of the Ogham was recognised as a mantric sound that shaped a particular creative force both in nature and in the psyche. Through harmonic resonance, these creation codes were recognised as the actual formative energies that manifest the landscape itself. Undulating sound waves, like the mythic rainbow-serpent, crystallise to become mountain ranges, hills, rivers, valleys and so forth. These waveforms are the so-called Songlines, reproduced by the shaman-bard on hearing the Earth ‘speak’ in the channelled language of spirit. The rising and falling of notes in tonal sequence synchronize with the shape of the sound waves, interpreting the topography of the geophysical environment as ‘frozen music’.

Sound travels through stone remarkably well, and the Earth resonates to harmonic keys. From the power-points and sacred sites (the original ‘bardic chairs’), the Orphic Bards transmitted specific frequencies along the serpent leylines, thus governing the realm by maintaining peaceful and harmonious vibrations throughout the land. The ground-plan of Herefordshire’s ‘Wheel of Perpetual Choirs’ is a good example of integrating sacred geometry – another aspect of musical ratio harmonics, also incorporated into temple architecture designed to resonate as ‘symphonies in stone’. Sacred structures, landscapes and even biological organisms are today verified by science as being sustained by sub-sonic morphogenetic fields. Inaudible frequencies may even have been used to move or even levitate large blocks of stone into position. Thus for the modern bards, there is still very much to learn from the Dreamtime ancestors of our native Druid land.

Initiate membership

Gorsedh Ynys Witrin has various levels of membership. The general membership (sometimes called The Outer Order or ’Gatehouse’ level) consists of all the uninitiated members, the minstrels and troubadours, the pipers, guitarists, drummers and comedians who have taken the Vow Of Kinship but not yet proven themselves as poets, musicians or heralds (storytellers) and taken the Awen initiation.

Students would be expected to practise the Seven Star Points and the Seven Precepts of Merlin, and study the Seven liberal Arts and sciences in preparation for their mystery training. This would be rather like a studying a foundation course.

Students would be expected to practise the Seven Star Points and the Seven Precepts of Merlin, and study the Seven liberal Arts and sciences in preparation for their mystery training. This would be rather like a studying a foundation course.

The Seven Star Points

- Honour

- Truth

- Justice

- Faith

- Liberty (Hope)

- Love

- Benevolence (Charity)

The Seven Precepts of Merlin

- Labour diligently to acquire knowledge, for it is power.

- When in authority, decide reasonably, for your authority may cease.

- Bear with fortitude the ills of life remembering that no mortal sorrow is perpetual.

- Love virtue, for it brings peace.

- Abhor vice, for it brings evil upon us all.

- Obey those in authority in all just things, that virtue may be exalted.

- Cultivate the social virtues, so shall you be beloved by all.

The Seven liberal Arts and sciences

- Grammar – the key to the understanding of speech

- Rhetoric – the art of speaking eloquently

- Logic – the science which leads us to form clear and direct ideas and the attainment of truth and knowledge

- Arithmetic – the properties of numbers

- Geometry – 3D mathematics, point to line to surface to solid, the foundation of architecture

- Music – the science of affecting passions by sound, harmony and hallelujahs

- Astronomy – the laws that govern the heavenly bodies

The Awen

The Awen is the central symbol of Druidism. It is formed by three rays of light and sound, which represent the three drops of wisdom that flew out of Ceridwen’s cauldron and provided Taliesin with divine inspiration. It is also known as the Mystic Mark. It represents the triplicity of all things: Love, Truth and Justice; God, Goddess and their sacred marriage; The three pillars of memory and history: vocal song, letter and symbol, or in fact, pretty much any triplicity you can think of, Christians might want to see it as Father, on and Holy Ghost. It is also used geomantically to mark the alignments of the sunrise points. It is used to invoke divine inspiration from the Muse.

The Awen is the central symbol of Druidism. It is formed by three rays of light and sound, which represent the three drops of wisdom that flew out of Ceridwen’s cauldron and provided Taliesin with divine inspiration. It is also known as the Mystic Mark. It represents the triplicity of all things: Love, Truth and Justice; God, Goddess and their sacred marriage; The three pillars of memory and history: vocal song, letter and symbol, or in fact, pretty much any triplicity you can think of, Christians might want to see it as Father, on and Holy Ghost. It is also used geomantically to mark the alignments of the sunrise points. It is used to invoke divine inspiration from the Muse.

Awen is a Welsh word derived from the Indo-European root ‘uel’ meaning ‘to blow’. It has the same root as ‘Awel’ the Welsh word for breath. There is a related word in Irish ‘ai’ which also means ‘poetic inspiration’.

The Awen is invoked by singing the three sacred syllables of I, A and O, which can be intoned as an invocation of divine inspiration from the Muse. These are the seed sounds of the creation of the universe, in a similar fashion to the Hindu ‘Aum’. The ‘i’ is pronounced like the “ee” in in “see” this represents the masculine, the creative force, which moves into ‘aa’ the feminine, the receptive, and the ‘oo’ represents the ecstatic union of male and female, of God and Goddess, that gives rise to manifestation.

The Bardic College

The Initiates are the Bards proper. On taking the Awen Initiation, candidates are enrolled as Anruth or probationary Bards. After a year and a day, they progress to the level of Prydydd.

The Initiates are the Bards proper. On taking the Awen Initiation, candidates are enrolled as Anruth or probationary Bards. After a year and a day, they progress to the level of Prydydd.

There are three main schools of Bardism:

- Poets – including Historical or Antiquarian Bards and Domestic or Parenetic Bards

- Musicians – including Harpists, Crwth players and Singers

- Heralds – including Storytellers

The only other grades recognised are those of Chaired Bard and Elder Bard (Pencerdd). The grades of initiate membership are administered by the Elder Bards and are only relevant to the collegiate structure of esoteric studies. All members of the Bardic Council are equal in status and voting rights, with a casting vote being held by the Chair.

Poetry

The school of poetry would teach Bardic meter and rhyming schemes. There are approximately 120 forms of meter in the Irish Gaelic system, somewhere around 2 dozen in the Welsh, roughly divided into Awdl (Odes), Cywyddau and Englynion (Englyns). In the Welsh tradition there is a separate Bardic Crown awarded for the best free verse of not more than 200 lines (Pryddest) – The Chair is awarded for the best strict metre verse of not more than 200 lines (Cynghanedd).

The school of poetry would teach Bardic meter and rhyming schemes. There are approximately 120 forms of meter in the Irish Gaelic system, somewhere around 2 dozen in the Welsh, roughly divided into Awdl (Odes), Cywyddau and Englynion (Englyns). In the Welsh tradition there is a separate Bardic Crown awarded for the best free verse of not more than 200 lines (Pryddest) – The Chair is awarded for the best strict metre verse of not more than 200 lines (Cynghanedd).

The rhythmic flow of a piece can be broken up using cross consonance and internal rhymes. Bards are also expected to know and use: assonance, alliteration, puns, verbal symbolism, consonant and vowel sound groupings. The technique of Cynghanedd combines several of these disciplines. Two halves of a line of poetry are balanced using repeated consonant patterns and internal rhyme. The Bards also used a system of Kennings, which are poetic paraphrases. Bards were expected to play with words and frequently made references to other stories using verbal symbolism or poetic shorthand.

Bards used a system of euphony (the science of seed sounds) which was encoded in the poetic correspondences of the Ogham (tree alphabet) cycle. Each letter of the old Irish alphabet corresponds to a tree, bird, gem, animal, faery being, colour, word, skill, castle and constellation. These follow an alliterative naming scheme in the early Irish Gaelic language. A Bard should be able to identify all native species of trees, animals and birds, know their practical uses, magical lore, divinatory meaning and their station in the Ogham cycle – the Druidic medicine wheel.

Music

The school of music would have taught music theory and musical performance skills. A Bard would be familiar with the Greek Modes and the use of cadences to create mood. They would have an understanding of rhythm, relating to both dance and trance induction. Ideally the Bard should play at least one instrument proficiently, but this has not always been the case. The Welsh favoured the harp (telyn), but also used primitive violin or crowd (crwth), pipes (pibgorn) – like the cor anglais, (it originated on the isle of Anglesey), tabor (tabwrdd) and the bugle (corn buelin) – made from the horn of a buffalo or wild ox. The Bard must be able to sing and improvise on a musical theme.

The school of music would have taught music theory and musical performance skills. A Bard would be familiar with the Greek Modes and the use of cadences to create mood. They would have an understanding of rhythm, relating to both dance and trance induction. Ideally the Bard should play at least one instrument proficiently, but this has not always been the case. The Welsh favoured the harp (telyn), but also used primitive violin or crowd (crwth), pipes (pibgorn) – like the cor anglais, (it originated on the isle of Anglesey), tabor (tabwrdd) and the bugle (corn buelin) – made from the horn of a buffalo or wild ox. The Bard must be able to sing and improvise on a musical theme.

Storytelling

The school of Heraldry taught the genealogies. A Bard was required to memorise and tell all the important stories of the tribe and to compose and perform pieces about current events or on a given theme.

Bards should show a good knowledge of traditional legends and lore, starting with the Mabinogion, including faerie tales, fragments of shamanic lore and ‘stories about important happenings at particular places’. They would probably have been expected to know Irish and Greek myths too.

There are only a few truly historical texts, namely; “The Triads”, “The Book of Taliesin”, “The Book of Aneirin”, “The Black Book of Carmarthen”, “The Red Book of Hergest” and the “White Book of Rhydderch”. Modern texts also worth studying include; “Barddas”, Frazer’s “Golden Bough”, Robert Graves’ “White Goddess” and Eleanor Merry’s “The Flaming Door”. Much of these later works is rather fanciful and is not considered to be authoritative, indeed the Bardic / Druidic tradition was known to be oral and philosophical, therefore all writings must be considered open to debate. The other major sources of clues are in the folk and sea-song tradition, nursery rhymes, place names, faerie stories and the carolling and Morris traditions. Fortunately there is plenty of material available in various Internet archives such as these:

The Roots of Druidry

The Bards form one college of the Druidic university, Ovates and Druids being the other two. Druidry is a nature-based philosophical path rooted in shamanic practice. Central themes are veneration of land, sea and sky and the ancestors, which are explored through metaphors of nature. Druidry does not require belief in God, gods, goddesses or godlessness and as such it can provide a focus for people of many different faiths or non-faiths to come together and affirm peace. Everything is seen as a process or continuum and since nothing, not even God, has any fixed, defined essence, there is no subject which cannot be discussed within the terms of Druidry.

The Bards form one college of the Druidic university, Ovates and Druids being the other two. Druidry is a nature-based philosophical path rooted in shamanic practice. Central themes are veneration of land, sea and sky and the ancestors, which are explored through metaphors of nature. Druidry does not require belief in God, gods, goddesses or godlessness and as such it can provide a focus for people of many different faiths or non-faiths to come together and affirm peace. Everything is seen as a process or continuum and since nothing, not even God, has any fixed, defined essence, there is no subject which cannot be discussed within the terms of Druidry.

The mind is not considered to be a thing, it is a process or mental continuum, within which the act of observation is more fundamental than the division into subject and object. Mental processes interact with and affect ‘physical’ processes at all levels of reality. Druidry sees reality in terms of three types of dependent relationship:

gwyar – causes and conditions; change, causality, element of water.

gwyar – causes and conditions; change, causality, element of water.- calas – the relationship of the whole to its parts and attributes; structure, element of earth.

- nwyfre – mental imputation, attribution or designation; consciousness, element of air.

The triskele represents reality arising from these three dependencies and may have been used as a meditation symbol by the Druids.

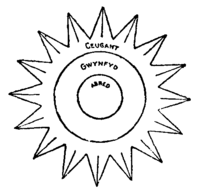

Three Circles of existence

Ceugant: where there is nothing but God.

Ceugant: where there is nothing but God.- Gwynfyd: Where all things spring from life. (Heaven)

- Abred: Where all things are derived from death. (Annwn)

The currently unimaginable completeness to which all things are ultimately destined is called Gwynfyd.

There is no anger which will not at last be pacified

There is nothing beloved lost which will not at last be returned

There is no soul born which will not at last attain the perfection of Gwynfyd

Druidism tends to be both Monistic (all is one) and Pantheistic (all things contain divine spirit). This is contrasted with the Dualism of the Christian God / Devil partnership and the Polytheism of Classical cultures. Celtic beliefs, particularly the faerie faith, derive from ancestor worship and we are told that they believed in reincarnation. Each clan would have it’s own totem spirits whose names were kept sacred to the clan.

In every person there is a soul,

In every soul there is intelligence:

In every intelligence there is thought,

In every thought there is either good or evil:

In every evil there is death:

In every good there is life,

In every life there is God.

The Wheel of the Year

In Glastonbury we celebrate the eight modern seasonal festivals, consisting of the two solstices, equinoxes and four cross-quarter days. The precise dates of these festivals, particularly the cross-quarters are constantly under discussion, some people prefer to synchronise them with lunar phases or hold celebrations exactly six and a half weeks apart. This means that in actual practice, the festivals tend to go on for about a week and Winter Solstice extends into the Christmas period with the main events being held on the closest weekend to these dates.

Beltaine and Samhain are the oldest divisions of the year, being the times when cattle were moved between summer and winter pastures. The ancient Celts split the year into three parts originally with the introduction of Imbolc to celebrate the lambing season. Lughnásadh was a later development as the agricultural harvest increased in importance. The Solstices were not observed until Dark Age times and the Equinoxes are likely to be a relatively modern invention to complete the wheel. Each clan would have its own private variation on the names of the festivals, which would be passed on as part of their hereditary knowledge.

The table below lists the Celtic language names for these festivals. The modern Wiccan terms were introduced by Aidan Kelly in the 1970s, the modern Druidic ones were dreamed up by Iolo Morgannwg in the late 18th century. The extinct Gaulish terms are reconstructed from information in the Coligny Calendar and as such are highly speculative. Additions and corrections from native speakers of these languages are welcomed.

| Date | Dec 21st – 25th | Feb 2nd – 4th | Mar 20th – 25th | Apr 30th – May 6th | June 21st – 24th | July 31st – Aug 7th | Sept 21st – 29th | Oct 31st – Nov 7th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiccan | Yule | Imbolc | Ostara | Beltane | Litha / Midsummer | Lughnasadh | Mabon | Samhain |

| Druidic | Alban Arthan | Alban Eilir | Alban Heruin / Alban Hefin | Alban Elfed | ||||

| Welsh (Cymraeg) | Canol Gaeaf / Heuldro’r Gaeaf | Gwyl Ffraed / Gwyl Olau / Gwyl Mair Dechrau’r Gwanwyn / y Canhwyllau | Canol y Gwanwyn | Calan Mai / Cyntefin | Gwyl Ifan / Gwyl Canol yr Haf / Heuldro’r Haf | Gwyl Awst | Gwyl Fihangel / Gwyl Canol yr Hydref / Cyhydnos y Hydref | Nos Galan Gaeaf / Hollantide |

| Cornish (Kernewek) | Howlsav an Gwav / Montol | Kehesnos Gwaynten | Cala Me | Golowan / Metheven | Gool Est | Guldize / Gooldize / Goeldheys | Nos Galan Gwafand / Calan Gwaf (Allantide) | |

| Breton (Brezhoneg) | Goursav-heol Goanv | Gouel Varia ar Goulou | Goursav-heol Hanv | Kala-Mae | Golowan / Gouel Sant-Yann | Gouel Sant-Mikael | Kala-Goanv | |

| Gaulish | Deuriuos | Ogronia | Giamonia | Medio-saminos | Aedrinia | Trinouxtion Samonii | ||

| Old Irish | Imbolg / Oimelc | Beltain / Beltene | Lughnasa / Lughnasad / Lughnassadh | Samain / Samuin / Samfuin | ||||

| Modern Irish (Gaeilge) | Grianstad an Gheimhridh / Cuidle | Imbolc | Cónocht an Earraich | Bealtaine | Grianstad an t-Samradh | Lughnasadh / Lá Lúnasa | Cónocht an Fhomhair | Samhain |

| Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) | Bealltainn / Bealtuinn | Lùnastal | Foghar | Samhuinn | ||||

| Manx (Gaelg / Gailck) | Boaltinn / Boaldyn | Sauin |

In addition to these dates, we also celebrate:

- March 1st

- St. David’s Day

- March 5th

- St. Piran’s Day

- March 17th

- St. Patrick’s Day

- May 19th

- St. Dunstan’s Day – Patron saint of Glastonbury

- June 17th

- St. Hervé’s Day – Patron saint of Bards

- Jan 17th

- Old 12th Night – Wassailing

Y gwir erbin y byd!

An gwir erbin an bys!

Truth before the world!

/|\

the ancient trees of elder within the seed of life

the acorn is the tree all is one to see